You already know that stress is an epidemic in American classrooms and homes. As parents, caregivers, and pediatricians, you’re aware that toxic stress has long term impacts on a child’s development, behavior, and health. While pediatricians, nurses, staff, and most of all children proved through the COVID-19 pandemic that resiliency is a powerful skill, stress and burnout still exists: for kids and their pediatricians. Pediatricians are strong, but many still aren’t sure how to talk about anxiety, depression, and burnout in concrete ways with their patients, let alone themselves. Dr. Jennifer Gray weighs in on strategies pediatricians can get better at the vocabulary of mental health for their kids, making all of our communities healthier in the process. Plus, a study on stress shines a light on how pediatricians are battling burnout.

On the Front Lines of Mental Health Care

Dr. Jennifer Gray, MD FAAP is a pediatrician at Pearland Pediatrics in Pearland, Texas, and she says that even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, she was concerned about the rapidly rising number of her patients with mental healthcare needs and the barriers that were preventing proper treatment.

“For me, I already had a fair amount of understanding about mental health,” she says. “I had some access to mental health resources, but there were more and more barriers. The timing of the class was ideal because of COVID.”

Dr. Gray is referring to training that she underwent via the Reach Institute in August 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The practice was shut down, and she had heard of the Reach Institute’s mental health training for pediatricians through word of mouth. She felt it was well advertised and had been rated well by other physicians, so she took the leap out of a desire to learn more about the management of mental health.

“It was their first virtual class,” she recalls, “It was on Zoom, but it was set up very well. It was a hands-on workshop that took the whole weekend.”

The results of that weekend were impactful and immediate. Dr. Gray left the training with not only an arsenal of screening tools, resources, apps, and books to further educate herself and her patients, but also a renewed sense of confidence.

Up until recently, medical school and residency programs have delved relatively little into the nuts and bolts of treating children for mental health. While every program is slightly different, many pediatricians anecdotally share their frustration at not having had further training in mental health prior to the mental health emergency announced by the American Academy of Pediatrics and others in 2021.

“I probably won’t be remembered for treating your child’s cold, but I’ll be remembered for treating their MDD or ED or guiding your teen to success. That will be way more of a reward.”Dr. Jennifer Gray, MD FAAP

Dr. Gray is just one of many pediatricians who felt that even with her years of hands-on experience in treating children, she wanted just a little bit more knowledge and context of mood disorders and common mental health issues to help serve her patients better.

That little bit more knowledge is the gap that the Reach Institute aims to fill. According to their website, the Institute began when their founder, Peter S. Jensen, MD “saw a widening gap between scientific knowledge about mental health and the application of that knowledge to help children and teens.”

The Reach Institute’s Patient-Centered Mental Health in Pediatric Primary Care (PPP) program is just one supplemental resource available to pediatricians seeking to expand their mental healthcare repertoire. Dr. Gray’s review is glowing.

“It was very interactive, with groups of 8 to 10 people with cameras on. There was lots of roleplaying. They would guide you through a screening tool and then have you practice using the tool and practice the conversations you would have with parents and patients.”

“They would challenge you to consider, ‘How would I handle X or Y?’ It was so great. It required very active participation, and I think it was unique in that it was so interactive.”

The course gave an overview of anxiety, depression, and ADHD, with a focus on medication management, cognitive therapy, overview of screening tools, and indicators that might warrant psychiatry support. After the weekend workshop, the cohort met every 2 weeks for about six months to share their real-world cases in the field and improve their knowledge as a community. Dr. Gray feels this program is a real supplement to medical school, like a “mini fellowship.”

She also says that having a solid foundation of mental healthcare knowledge and community to call upon helps reduce barriers in her patients’ access to care. “As PCPs, we know families so well. They’re more comfortable with us managing mental health care. Parents take it easier from us. As PCPs, we know our families very well. This makes it easier for families and patients to discuss sensitive concerns and provides a comfortable place for managing mental health care.”

Barriers to care may include stigma, difficulty finding psychiatric care in-network, travel, scheduling, and more, but Dr. Gray emphasizes that trust is a basic need for successful mental healthcare – a precious resource that pediatricians have in spades. The trust in the family pediatrician can make the sometimes practical, sometimes emotional barriers to mental healthcare easier to bear for families.

“It’s more convenient for families to receive mental care from our practice. They are already familiar with the patient portal and telehealth visits, which are easy ways for us to follow up on behavioral health treatments.”

Pearland Pediatrics is experiencing a shift towards proactive mental health care that may very well be a turning point in pediatric healthcare history, where pediatricians have a foundation in mental healthcare earlier in their education. For now, the learning is communal and interactive. “We’ve had two more doctors complete REACH,” says Dr. Gray. “We have scheduled mental health roundtables where our physicians come together over lunch to discuss diagnoses, patient cases, screening tools, and resources in the community that we’ve found helpful.

The feedback from Pearland Pediatrics’ community is positive. “We get good feedback from psychologists and parents.”

Still, Dr. Gray notes realistically that the Reach program did not solve all her concerns about caring for kids’ mental health – barriers still exist for kids who need referral to psychiatric services, for example – but overall, the experience was worthwhile.

“The number of mental and behavioral health visits on my schedule can feel overwhelming some days and there are challenges that still exist. But with the training and knowledge I gained from REACH, I am better equipped to manage these needs alongside families.”

When considering the future, Dr. Gray muses: will the day come when pediatricians are remembered for mental healthcare instead of physical ailments? She thinks so. “We are the medical home. It would be easier if you could refer out [to psychiatry]. Sometimes it needs to happen. But we need to step in, too. We’re the first face of this crisis, and need to be confident in managing mood disorders. You can’t screen for mental health conditions and then not take the ownership to manage them; we have a role in that space. We strive to see our patients become healthy adults, both emotionally and physically. I probably won’t be remembered for treating your child’s cold, but hopefully will be for prioritizing their mental health. Equipping young children and teens with the right tools for mindful, healthy living will be much more rewarding.”

“Absolutely the number one stress is the mental health cases I’m seeing. You could say, in our practice, Covid was the earthquake and now mental health issues are the tsunami.“Anonymous Pediatrician

Stress, Burnout, and Giving from an Empty Cup

Pediatricians are givers. They’re trained to be; as residents, they work hard for the right to wear that white coat. They specialized in pediatrics over many other disciplines. Many describe pediatrics as a calling – serving something greater than themselves. Many more simply want to help kids.

Independent pediatricians take it a step further and give of themselves into a small business so that they might practice the way they choose to, serving their communities as their predecessors did. Some pediatricians are parents; some are active members in clubs or churches; some serve on city councils; many work to change policy in government in all levels.

Pediatricians have always been givers, pouring care and attention and empathy from seemingly endless cups.

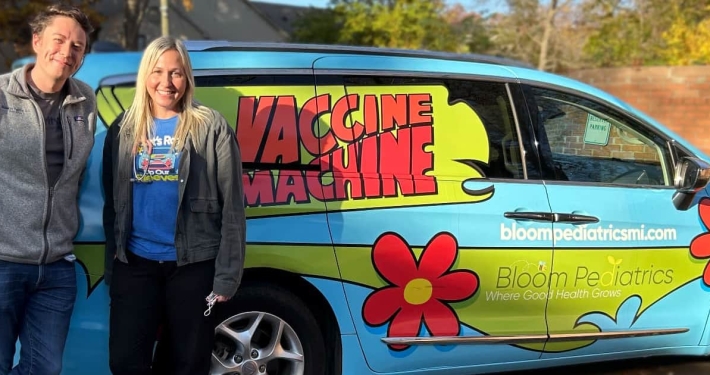

But the cups aren’t endless. And pediatricians of today have much more on their plates than they did even fifty years ago. Internet misinformation. Shifting healthcare insurance policies. Hospital buyouts. Anti-vaxxers. A growing crisis of mental health that, as we’ve just seen, many pediatricians weren’t and aren’t prepared for.

Many consider the COVID-19 pandemic the straw that broke the camel’s back – the huge stressor that revealed all of the ways pediatricians are struggling to keep their practices and their hearts open. Now that they’ve survived an incredible historical moment, many are wondering: when did I get so tired? Have I always been this stressed?

There are many reasons families are stressed, and pediatricians are stressed about their families’ stress. Children pick up on tensions from their adult caregivers and become stressed. It’s a cycle of stress that can lead to burnout, a ‘workplace phenomenon’ which the World Health Organization defines as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed,” and to compassion fatigue, a similar condition.

But there is more to physician burnout than the mental health crisis, and during the 2023 PCC Users’ Conference, PCC asked the Omansky Group to dig deeper. The result is a report that describes the stressors of ten anonymous respondents, ranging from online misinformation to the staffing crisis.

The most staggering part of the report from the Omansky Group’s perspective was the unanimity of the results. All ten of the respondents said that the most stressful part of their jobs was dealing with the mental healthcare crisis their patients are experiencing in real time.

“Absolutely the number one stress is the mental health cases I’m seeing. You could say, in our practice, Covid was the earthquake and now mental health issues are the tsunami.” – Anonymous Pediatrician

The report further explored how demands on pediatric practices are stressing out pediatricians as well as their staff, resulting in a staffing crisis as nurses and other staff members seek stability and security in other roles.

“We’re not getting all the patients seen who need to be seen, the staff keeps making demands on me and we just don’t have enough people to care for these kids.” – Anonymous Pediatrician

Respondents also listed misinformation as a big obstacle, having to come to the defense of their stance on vaccines, mental healthcare, and more from parents who are “armed and dangerous” from dubious sources of healthcare information on the internet.

“I get stressed when I have to spend time undoing the TikTok advice parents come in with, along with the front desk getting frustrated because there’s nowhere to put patients in the schedule because mental health visits take longer.” – Anonymous Pediatrician

“I’m responsible to meet kids’ needs and to give them what they deserve. The world is raining social and administrative barriers down on me. It’s impeding me from delivering what kids need. Those kids need me to help them, it’s raining so many barriers, I don’t feel I can give them what they deserve.”

These anonymous confessions are difficult to read: they’re a sign of pediatricians desperate for a lifeline, for some help, for change that meaningfully impacts their patients and sets their practices to an even keel. We have shared these confessions here for an important reason: while you may be struggling, you are not alone.

We have shared these confessions here for an important reason: while you may be struggling, you are not alone.

Filling the Cup: Addressing Burnout

“What separates people who love their job, believe it’s a calling, and cannot wait to return to the office from those who can’t stand to work another day?” This is the question Dr. Robert Trimble, MD FAAP, a pediatrician from San Antonio, TX, set out to answer in pursuit of understanding burnout better. What he found is both surprising and compelling: it’s not your fault.

The answer to burnout, he says, is that it is not a personal failing. It is not the lack of motivation, skill, grit, or any other virtue that makes others able to work longer hours with wider smiles for their patients and still coach their child’s soccer team and attend town board meetings and set up a vaccine clinic. Instead, Trimble says that pervasive physician burnout is a corporate, collective, and community problem that likewise requires collective solutions.

“The reason burnout is a real problem is that we as a group have done a poor job in the past of acknowledging what burnout is, accepting that the majority of us burn out, and not just labeling those physicians or providers as ‘weaker’ or ‘less stable’ or ‘less reliable.’ Burning out has elements of challenges within an organization and with the provider. It also changes as the demands on that person can change.”

He continues, “If we only focus on healing from a personal perspective, we are missing reducing organizational and individual stress sources and allowing for organizational recharge. We need to see it from all sides.”

Dr. Trimble’s ideas on burnout seem to be a modern physician’s version of Taoism, an ancient Chinese philosophy whose tenets include the concept of constant change, the path of least resistance, and acknowledging that we cannot change everything. “Change is ever-present in medicine and especially in independent practice,” he says. Perhaps it’s comforting to know that people as distant in time from us as 500 B.C.E. had similar stressors surrounding work, deadlines, and family concerns. Our modern lives are certainly busy, but at least as far as the human psyche is concerned, some things remain the same, such as gaining mental relief from reducing stress.

One way of reducing stress is taking a hard look at workflow obstacles. “Dealing with reducing organizational stress means improving your workflow time management and ability to get meaningful work done,” Dr. Trimble says. “Reducing organizational stress could mean streamlining your patient intake process, rooming patients, dealing with phone calls and requests, and handling refills and EHR work. It means delegating as many tasks as possible.”

Everyone experiences stress, but no one has to experience it alone. Through sharing the stories of Dr. Gray, the anonymous PCC physicians experiencing burnout, and Dr. Trimble’s sage advice, we hope to provide you with the tools and context to know that relief is possible. We’ll leave you with some final advice from Dr. Trimble:

“At some level, it is essential to realize what you can change and those things that you cannot… Learning and executing the latest quality care measures is much more difficult when the primary care provider is stretched too thin.”

Allie Squires is The Independent Pediatrician‘s editor and the marketing content writer for PCC. She holds a M.S. in Professional Writing from NYU, and BAs in Writing and Literature from SUNY Plattsburgh. When she’s not writing, she enjoys reading and exploring her adopted home state of Vermont.