Trust and Reassurance: Serving a Diversity of Patients in South Carolina

Dr. Eliza Varadi, the owner of Pelican Pediatrics in Charleston, South Carolina, is committed to making sure patients who may have been marginalized in the past have access to the health care they deserve.

Dr. Eliza Varadi, the owner of Pelican Pediatrics, speaks English, Russian, Hebrew and Spanish. A second full-time pediatrician speaks Spanish. The practice’s part-time pediatrician speaks Punjabi. The practice’s administrator, Vladimir Varadi (Dr. Varadi’s husband), speaks Russian, Estonian and German. Staff members are from Russia, Estonia, India, Mexico, Panama and Ireland. A part-time nurse practitioner is African American and she also speaks Spanish. The group represents three different religions.

The diversity of the team is intentional, says Dr. Varadi, as the patients they serve in Charleston, S.C., reflect a multitude of backgrounds and life experiences.

“It’s always been my goal to be able to serve as large and diverse of a community as I can,” says Dr. Varadi. “Especially a community that may otherwise be disenfranchised or left behind due to access or due to communication.”

As the largest city in South Carolina, Charleston draws in a plethora of recent immigrants thanks in part to a growing economy. Some seek employment in the hospitality field or building trades. Migrant workers have also long sought work in agriculture, South Carolina’s largest economic sector, according to the South Carolina Farm Bureau.

In her practice, Dr. Varadi sees many Mexican, Honduran, Venezuelan and Guatemalan families, as well as patients from Colombia, Brazil and Argentina. Since she speaks Russian, many from the region’s “pretty large” Uzbek population seek her out. Pelican Pediatrics also sees a large number of Israeli families. Varadi says the practice relies on word of mouth and referrals from current patients to reach families who may have in the past faced barriers in seeking out medical care. Their reputation as a welcoming place speaks for itself.

“When your friend tells you, ‘Hey, there’s a great pediatrician, there’s a great practice, and you’re going to feel at home, and you can trust them and they’ll take care of you, and they won’t treat you differently because you’re an immigrant or don’t speak English or are a different religion,’ I think your natural response is yes,” she says. “Maybe they haven’t really had that opportunity before.”

The team works hard to make sure families continue to feel heard and understood every time they walk through the door.

“We always have to do our best to try to be friendly and try to be understanding no matter what,” she says. “Then of course, as far as language, we have information in our office in different languages. Our Facebook posts are often in different languages. We have a map of the world in our office where people can put stars on the countries they came from.”

This work is important to make sure patients who may have been marginalized in the past have access to the health care they deserve. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children of immigrants are “nearly twice as likely to be uninsured as are children in nonimmigrant families,” and they are more likely to live below the poverty line. Thanks to language and cultural barriers, they are less likely to access the programs and benefits designed to help low-income children.

Dr. Varadi wants Pelican Pediatrics to be part of the solution.

“You have to build a rapport,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what language you speak. I think it’s a matter of reassurance and undoing the negative work that’s been done or that’s been set in their minds.”

“It’s always been my goal to be able to serve as large and diverse of a community as I can. Especially a community that may otherwise be disenfranchised or left behind due to access or due to communication.”Dr. Eliza Varadi

A Desire to Learn

Dr. Varadi knows the immigrant experience firsthand. She came to the U.S. from the former USSR with her family when she was eight years old. They landed in New York City, a place teeming with recent immigrants from their home country.

“[In New York it] was very, very hard to find work,” she says. “It’s always been a city where things are rapid and prices are high, but now you imagine millions of people coming there from the Soviet Union, most of whom had similar careers to one another. You can imagine that market being flooded. You had college professors now being janitors and dishwashers.”

When her mother was offered a job with the Charleston Symphony Orchestra as a violinist, they moved to South Carolina. The family found a strong support network in their new home city.

“The Charleston Jewish community really helped us a lot,” she says. “There weren’t very many people who moved here like us, so the resources were more directed. We were just very lucky.”

Still, they experienced hardship and discrimination. She recalls one incident shortly after their arrival in New York City. When her brother woke up with severe abdominal pain, her mother suspected appendicitis and called an ambulance.

“Obviously we had no insurance and we didn’t speak very good English,” she says. “They refused to take him to the hospital and it was in the middle of the night. My mom knocked on neighbors’ doors until she got one of our neighbors to wake up and drive him to the hospital. Sure enough, he had appendicitis.”

It’s not an experience relegated to the past, says Dr. Varadi. “Even to this day, unfortunately, I see patients who are immigrants, who may not have insurance or who may not speak great English, not receiving standard of care even at our local hospitals,” she says.

“I am an immigrant, but you don’t have to be to serve a diverse population. You just have to have interest and desire to learn and be open minded.”Dr. Eliza Varadi

Dr. Varadi’s path to medicine funnels in part through two key mentors: her grandmother, a psychiatrist in St. Petersburg, Russia, with whom she lived as a child, and Dr. Lyndon Key, OBM, a pediatric endocrinologist and researcher in the U.S. who treated her in her preteen years. He became a key reason why she chose to pursue medicine, and pediatrics specifically.

“He really helped me navigate from a high school senior thesis through college, through my decision to apply to medical school, and then even residency, where he wound up being my program director [for the first year],” she says.

Although she toyed with a career focused on scientific research, she ultimately decided that she enjoyed interacting with patients too much to spend her life in a lab.

“I had intentions of being a researcher, a scientist,” she says. “I was very interested in genetics. But when I started doing more of that in college, I realized I needed more social interaction.”

So she decided to become a doctor, attending The Medical University of South Carolina. When it came time to choose a specialty, she found herself torn between OB/GYN and pediatrics. Eventually, she gravitated towards children, a population she has felt drawn to throughout her life.

“All the jobs I’ve held were always something related to kids,” she says. “I used to work at Chuck-E-Cheese as a birthday party hostess. I used to coach kids’ gymnastics and beginner figure skating. I did a lot of tutoring for math and science for kids. Then in college, again, I tutored math, science, SATs. I also taught Hebrew school.”

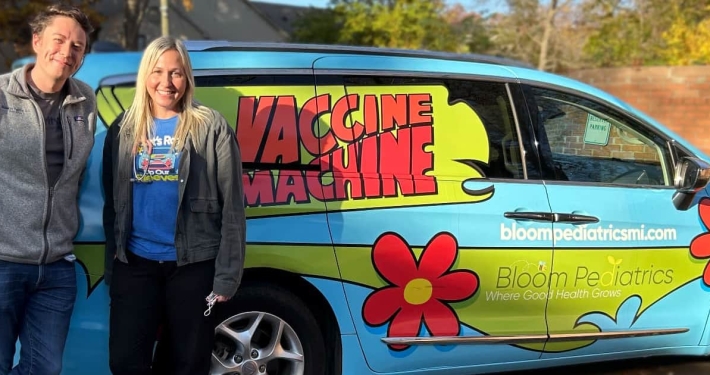

She completed her residency in pediatrics at The Medical University of South Carolina Children’s Hospital and four years later, founded Pelican Pediatrics in 2014. Now, the practice has expanded from what was initially a solo practice to one with a second full-time pediatrician and a part-time pediatrician. Her husband Vladimir, the practice’s manager and administrator, helped her to navigate the leap into running a business.

“He was the one that encouraged me to go out on my own,” she says. “I don’t know if I would have done it, or at least not four years out of residency. I definitely wouldn’t have done it that quickly, but I think he kind of pushed me into it because he thought that, between the two of us, we could do it.”

The Varadis have been steadily increasing the number of services they’re able to provide patients, based in part on what they see as emergent needs.

“We’ve been doing telemedicine since the pandemic started, so since March,” she says. “We’ve also co-located with services our patient population may not have easy access to, including mental health and speech therapy.”

The goal is to continue to stay accessible to the patients they’ve worked hard to bring in the door, which may mean putting a limit on growth for Pelican Pediatrics.

“I do not want a large practice,” she says. “I want to keep that small medical home model where you see the same people all the time, which I think is much easier to do if you are a small practice.”

Dr. Varadi also sees in her practice’s trajectory opportunities for others to follow a similar path, no matter their background.

“I am an immigrant, but you don’t have to be to serve a diverse population,” she says. “You just have to have interest and desire to learn and be open minded.”

“Don’t be afraid to go out into the community and let people know where you are, what you do, and that you are happy to serve them.”Dr. Eliza Varadi

The Pandemic’s Toll

Dr. Varadi has witnessed the unequal toll the COVID-19 pandemic is taking on immigrant families and patients from diverse backgrounds.

“During the pandemic, I think there’s definitely a disproportionate amount of illness in our Hispanic population,” she says. “A lot of people are in construction and gardening, and jobs where they carpool to work. Often, people who are positive or have been exposed and should have been quarantined continue to go to work because otherwise they’re at risk for losing their housing and their ability to survive.”

Carpooling to a job site — often a necessity in the Charleston area given a lack of public transportation or access to personal vehicles — adds another vector to the mix: if there’s “one positive in the car, there are five positives in the car,” says Dr. Varadi, which increases exponentially the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

She’s also seen troubling trends in the teenage population during the pandemic.

“Pretty much 50 percent of all our teenagers have had a need to see a mental health specialist,” she says. “Anxiety and depression went from being about 20 percent in the teenage population to being about 50 percent, which is a significant rise.”

She points to two reasons: first, a lack of socializing, which “at that age is very important.” And second, the trauma of seeing their families struggle financially and sometimes even fall ill from COVID-19.

“Especially in our immigrant population, we have a lot of multigenerational households, so there’s that constant fear that grandma or grandpa is going to get sick,” she says.

Unfortunately, the economic fallout from the pandemic often leads to a cascade of negative consequences, especially for those who are Hispanic or Latino. According to the CDC, Hispanic or Latino persons have 1.3 times the risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to the white/non-Hispanic population.

The numbers are even more stark when it comes to hospitalization and death: Hispanic/Latino persons are 3.1 times more at risk for hospitalization and 2.3 times more at risk of death from the disease as compared to non-Hispanics. A constellation of “risk markers” influence these numbers, including “socioeconomic status, access to health care,” and the fact that Hispanic/Latinos are more likely to hold jobs that can’t be done remotely. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that those who are Hispanic/Latino are overrepresented in jobs in construction, maintenance, groundskeeping, and housekeeping. Little job protection means choosing between staying home to prevent illness and missing pay or losing a job.

Women who are Hispanic/Latina have been hit hardest of all. According to the Center for American Progress, Latina workers have “seen the worst employment data of any racial/ethnic and gender group during the coronavirus-induced recession,” with an unemployment rate of 20.1 percent in April 2020. This isn’t only due to job loss; they are also “leaving the labor force at greater rates than Hispanic or Latino men because they have shouldered more of the increased caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic.”

The ripple effects extend to children, says Dr. Varadi. When parents are struggling to keep their jobs, “the older kids are often taking care of the younger kids as the parents are still trying to work,” says Dr. Varadi, adding to their stress and anxiety. Rates of food insecurity rise as families attempt to make ends meet while navigating job loss or a decrease in work hours. All of this weighs against the mandate to quarantine if exposed to someone diagnosed with COVID-19, forcing very difficult decisions for many families.

Pelican Pediatrics is doing what they can to help through offering important resources.

“We do test both parents and kids, because testing is still harder than it should be in South Carolina, especially if you don’t speak excellent English, and especially if you’re not very internet savvy,” says Dr. Varadi. “A lot of our testing registrations are done online. And many urgent care clinics are doing a lot of for-profit testing, charging a lot more than they should be charging.”

Long-term, Dr. Varadi sees hope in universal health care, especially for children.

“Obviously, adults are important as well, but kids have really no way to protect themselves,” she says. “Everybody can agree that all children deserve full opportunity, and we know that if you’re unable to stay well, you don’t have full opportunity.”

For other practices looking to reach diverse populations in their communities, it’s important to meet potential patients where they are, says Dr. Varadi. Seek them out and invite them to learn more about your practice and your approach to patient care.

“Don’t be afraid to go out into the community and let people know where you are, what you do and that you are happy to serve them,” she says. “Volunteer at health fairs for immigrants or some of the other local health fairs or schools.”

Ultimately, the goal is to be present for all patients, especially those who may have been left behind in the past. Pelican Pediatrics accomplishes this by staying true to its roots and tailoring the practice to the needs of the people it serves.

“We try to stay small, almost like a mom and pop practice. I think it’s easier to provide good medicine because things are not getting lost in the shuffle of paperwork and lots of people,” says Dr. Varadi. “It’s about forming that relationship and that trust and making sure that, not just the physician, but everybody in the practice is part of forming that bond.”

A resident of Burlington, VT, Erin Post has a BA degree in English from Hamilton College, and is a graduate of the writing program at the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies. She is currently working on her master’s in public health at the University of Vermont. In her spare time, she likes to bike, ski, hike, and generally enjoy the Green Mountains of Vermont.