From the University of Nigeria to her independent practice in Georgia, Dr. Nneka Una shares important lessons from a rich career in medicine. She offers her approach to independent practice management, whole-child care, and professional coaching—an approach that is grounded in strong relationships and education.

Practicing with Personality

Dr. Nneka Unachukwu—or Dr. Una, as her patients and colleagues call her—strives for excellence in all that she does. The very name of her practice communicates her commitment to quality. “Our practice is called Ivy League Pediatrics because the quality of care that we give is nothing short of excellent,” Dr. Una says. “The name is there because that’s what we strive to be.” And then, with a playfulness that characterizes many of her reflections, Dr. Una adds, “And you know, I was educated at the University of Nigeria, which is the Ivy League of Nigeria,” she laughs. “But the main reason behind the name is to reflect the level of service that we offer.”

In addition to her M.D., Dr. Una has enough nonclinical side projects to warrant a resume of secondary titles. She is a pediatrician, but also a professional coach, teen counselor, and writer. Dr. Una describes her path to independent pediatrics, her myriad nonclinical passions, and how she manages her interests and projects while leading a balanced life.

An Advocate for Whole-Child Care

Before landing in Georgia and opening Ivy League Pediatrics in 2010, Dr. Una studied medicine at the University of Nigeria, then went on to complete her pediatric residency at the Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in New Jersey. “I knew I was going to be a doctor, but funnily enough, when I got into medical school I assured everyone I was not going to be a pediatrician,” she recalls. “At first I settled on OBGYN, because I was passionate about working with mothers. But when I started my residency I realized it would be unsustainable to do 24 hour calls for the rest of my life. That’s when I decided to slide over to pediatrics. I thought, I’ll partner with mothers to take care of their kids.” This philosophy of partnership is evident in Dr. Una’s practice. Her approach unifies physical health, mental health, and both parent and child education to promote the best outcomes for her patients.

Dr. Una recognizes that her visit time with patients is limited, so she strives to build relationships with her parent community, recognizing that if she wants to change kids’ habits, educating parents is more than half the battle. She cites these relationships as essential components of whole-child care. “A lot of parents really second-guess themselves,” Dr. Una says. “It’s overwhelming to have this little person, and you’re responsible for them. It happens once or twice a week where a parent comes into the room crying that they’re ‘breaking’ their kid. Taking care of the kids means caring for mom as well.” Dr. Una takes the time to coach confused or overwhelmed parents, integrating “caring for mom” into her practice of caring for kids.

When asked which specific medical issues warrant an examination of habits, Dr. Una cites childhood obesity and ADHD as two specific areas of interest and concern. A closer examination of her approach to these widespread issues yields a deeper understanding of Dr. Una’s approach to whole-child care and wellness.

“Our goal as a practice has always been to provide expert medical care with unparalleled customer service in a timely fashion. If you look at our reviews, you see that there’s a theme. We’re warm, we’re friendly, we get people in and out on time.”Dr. Nneka Una

Fighting Obesity with the Whole Family

One of Dr. Una’s clinical focal points is childhood obesity, an issue for which she notes that parental buy-in and participation is of the utmost importance. “I’m passionate about helping families fix obesity because I see where this issue is going and it’s not pretty,” she says. “But if the parents aren’t on board, it’s extremely challenging for me to help.”

Dr. Una relays some disturbing anecdotes about childhood obesity that she’s noticed at her practice. “I used to have kids who were maybe 10 or 15 pounds overweight. Now, I have kids who go to stay with grandma for the summer and come back 30 pounds heavier.” She continues, “The amount of weight that kids are putting on is ridiculous. I’ve had patients come into my office at the age of three weighing 52 pounds; a four-year-old at 84 pounds; fifteen-year-old at 217 pounds.” Dr. Una comments that, on a national scale, “The childhood obesity epidemic is a precursor to an unhealthy adult population. This is a huge problem that’s going to cost the country billions and billions of dollars.”

While of course there are many factors—social, economic, and genetic, among others—that contribute to obesity, Dr. Una cites screen time as one of the primary accelerators of childhood weight gain. “The average American child, eight years old and up, spends seven hours on electronics a day. And that’s just leisure time, not doing schoolwork,” Dr. Una says. “The first time I read that number in a CDC study I thought it wasn’t possible, so I started asking parents in my practice and they confirmed—it’s possible.” However, Dr. Una offers a solution: “With some of these kids, if I can get the parents’ buy-in, we can reverse the trend.”

Dr. Una’s approach focuses on equal parts diet, technology usage, and movement. “The first step is to get the parents on board to clean up the diet,” she says. “Some of my patients eat fast food every day, twice a day. I’ve met a three-year-old who has never had water in her life, only juice and milk. Just supplementing those liquids with water, the child loses weight.”

The next step, one that can be arguably more difficult, is to get kids to disengage from technology. “Reduce screen time to two hours a day,” says Dr. Una. “Kids by nature move nonstop, but when you give them technology, they sit. It used to be that in the summers, everyone would lose weight because kids would play outside all day. Now the new playground is the iPad. And you don’t lose weight playing on your iPad.”

Before Dr. Una can tackle diet and technology usage she needs parents on her team. “When the parents’ buy-in isn’t there, there isn’t much I can do besides continue to educate. Without commitment from the parents you can’t pull it off,” she asserts. “But if you can help a family fight obesity, you just gave them a clean slate. We can save kids from premature hypertension, diabetes, and joint problems; save them from the risk of being bullied at school and having low self-esteem; we prevent cancers and high cholesterol. It’s not just the weight. You fix all these other problems that complicate their futures.”

ADHD Diagnosis and Treatments

Dr. Una sees a number of patients with attention and executive functioning issues. “There’s a lot of stigma around ADHD,” she says. “A lot of parents feel really guilty if they have to medicate their child. They feel like failures as parents.”

Of course, this proliferation of both diagnoses and worries is far from unique to Ivy League Pediatrics. The National Resource Center on ADHD, CHADD, reported in a 2016 survey that 6.1 million children in the U.S. between the ages of 2-17 have been diagnosed with ADHD.1 The American Psychological Association (APA) reported in a 2014 article that between 2003 and 2007, there was a 22% increase in ADHD diagnoses nationally of children between the ages of 4 and 17.2 The APA also states that, “The Center for Disease Control (CDC) found that over two-thirds of children and teens who have been diagnosed with ADHD take medication for it.”

“If you walk in with your 16-year-old kid who’s been a straight-A student his entire life and you tell me he needs Adderall for ADHD, I won’t prescribe it. I’ve had parents leave the practice because of it—because I won’t write the prescription.”Dr. Nneka Una

Aware of this trend, Dr. Una strives to be discerning in her diagnosing and prescribing. “I know there are unnecessary prescriptions when kids are under a lot of pressure to perform at a high level and to get into certain colleges, for example,” she says. “At my practice we don’t subscribe to that. If you walk in with your 16-year-old kid who’s been a straight-A student his entire life and you tell me he needs Adderall for ADHD, I won’t prescribe it. I’ve had parents leave the practice because of it—because I won’t write the prescription.”

Dr. Una shares her theory on the surge of behavioral-correcting medication prescriptions over the past few decades, although she gives the caveat that her hypothesis is based mostly in anecdotal evidence. “With the collapse of the family system, and with the rise of social media, I’ve seen behavioral problems in general skyrocket,” she says. “There aren’t pills to fix some of these things that children are struggling with today.”

On the other hand, Dr. Una works with parents who are wary of medications and would prefer non-medical treatment for ADHD. “Parents are scared of the medication, or they feel they’re not doing a good job as parents and that’s why their child is struggling,” she says. “I’m a minimalist as far as prescriptions go. However, if you have a kid who’s been struggling for years and is not learning, medication can be extremely helpful.”

“I don’t have a non-medical way of fixing ADHD yet,” she continues. “When I do, my patients will be the first to know. As of now, we use the smallest amount of medication we can to get the results we need. What we want is to give these children a chance to excel. It’s rewarding to see the kid who’s been a straight-D student go to the gifted program after getting to the heart of the problem.” Regardless of medical treatment, Dr. Una stays engaged with families from the moment their child is diagnosed with ADD/ADHD until she can track their success with concrete outcomes.

Advice for Starting an Independent Practice

“When I started my practice, it was the scariest thing I’d ever done in my life,” Dr. Una admits. “As physicians, we are trained for over a decade to be great clinicians, but we know nothing about the business of medicine. We feel guilty talking about money. We hear that our hearts’ desire should be to serve our patients, which of course it is. But if you aren’t successful as an entrepreneur and you have to shut your clinic down, you can’t serve your patients.”

To find success in opening her own practice, Dr. Una says, she “kept her doctor hat on” in the clinical setting, but otherwise, “I treated it as opening my first small business. I educated myself. I did a lot of reading, attended courses. I sought out mentors who had opened their own practices. And then of course there was the School of Hard Knocks,” she laughs, “and I’ve had my fair share of knocks.” Dr. Una has learned to unify self-awareness with a sense of humor that is both infectious and admirable. Her ability to laugh seems to be a part of her life philosophy, and it’s also integral to her success. Maintaining her sense of humor is one strategy for maintaining work-life balance. “I will always do my best in my professional life, but I also want to be a happy human being,” she says.

Global Education, Global Approach

Following an international education and residency in New Jersey, Dr. Una landed in Lawrenceville, Georgia, where she opened her practice. “I picked Georgia for no other reason than that New Jersey is too cold!” says Dr. Una. “My tropical self couldn’t take it. I knew I wanted to be here just out of intuition.”

Dr. Una’s international background shows up not only in her approach to teen coaching or the location of her practice, but also in specific services at Ivy League. For example, Ivy League Pediatrics offers ear piercing on-site. “There’s a major cultural reason behind it,” Dr. Una explains. “In Nigeria, when a baby girl is born she gets her ears pierced in the hospital before she goes home. This happens in the newborn period. In Nigeria, if you show pictures of a baby girl without the ears pierced people wonder what went wrong,” Dr. Una says with a laugh.

Ivy League’s ear piercing service is available to anyone in the community, not just patients of the practice. Dr. Una sees the value of this option as a parent as well. “When I wanted to get my daughter’s ears pierced the only option I had close by was to go to the mall!” she exclaims. “And I thought, ‘There’s no way I’m taking my child to the mall for some 17-year-old to practice ear piercing for the first time on my daughter!’” Dr. Una continues, “My own experience helped me recognize a need that other cultures have as well, for things that aren’t widely available in a medical setting in the U.S. In Lawrenceville I serve a diverse population where it’s common for girls to have their ears pierced at a young age. Parents want to do the piercing early, but they don’t want to take their one-year-old to the mall.”

Comparing the University of Nigeria to medical school in the U.S. with broader strokes, Dr. Una mentions the differences in technologies available to doctors and medical students. “One of the major differences that I perceive is technology,” she notes. “When I went to medical school in Nigeria certain technologies were simply unavailable, so you really had to depend on your clinical skills, perhaps more than you’d have to in the U.S. Here you can say, ‘You’re coughing kind of weird, get an X-Ray.’ In Nigeria, your patients are paying out-of-pocket so you’d better figure it out with your stethoscope and your patient history.” Dr. Una concludes that her education abroad has made her a more investigative and dynamic practitioner at home. More than finding a purely clinical solution to a health problem, Dr. Una is invested in building relationships and truly understanding her patients’ conditions on a holistic level.

Motivating Adolescents

Aside from professional coaching, Dr. Una has delved into coaching and counseling adolescents through an online project. She developed her interest and expertise in working with adolescents over many years, and much of her drive to work with this age group comes from personal experience. “Some of what I teach I learned as a pediatrician, but my motivation begins with my own story,” she explains. “When I was a teenager, I started learning about successful habits and investing in yourself. I went to medical school in Nigeria, which uses the European system. So you go straight from high school to six years of medical school.

I turned 17 in medical school!” She laughs, “which is something that would surprise many American practitioners. As an adult, I understand the value of using your youth wisely. If you can work hard when you’re young, you can play when you’re old. That consciousness is what drives me to push young people to invest their youth and not squander it.”

This passion led Dr. Una to develop the Virtual Leadership Academy, a project she’s “wanted to undertake for years.” The Academy is a four-week virtual course that, in Dr. Una’s words, is intended to “jumpstart teens’ curiosity about their future.”

“This summer was the launch of the program,” Dr. Una says. “The thought was that teens are going to be free for the summer months, and some of them are just going to sit on their iPads and phones the entire time. Students lose reading levels during the summer and are set back. I wanted to use this time to jumpstart some habits that will help them be successful as adults.”

She continues, “I knew if I made it a ‘class,’ teenagers would resist it. So I made a series of short videos, 10-15 minutes, where I talk about goal-setting, planning, and grit. The students make five-year goals, 12-month goals, learn how to do a daily to-do list, how to make a vision board… They learn how your habits can make and break you.” Dr. Una’s eye toward character goals are in line with some of the most up-to-date research and practices in education. In particular, the idea of “grit” stands out, which MacArthur Fellow Angela Duckworth defines as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals.”

By engaging with current thinking in education, Dr. Una is able to tailor online assignments to her students’ needs. In her “goals” video, students are asked to explore questions of purpose and motivation by crafting lists of their own goals. Small as the time commitment may be for kids, the Virtual Leadership Academy has set some participants on a new path. Dr. Una reports that parents will call her with testimonials. She describes a phone call from one mother who exclaimed: “Oh my god, my kid is reading! When they earn money, they’re saving it instead of blowing it! They cut their screen time down by hours! What happened? I don’t know what you did, but I have a brand new kid.”

The mother mentioned above is from the U.K. Though Dr. Una expresses some well-founded doubts about children’s dependence on the internet, she has put it to great use in both marketing and proliferating the Virtual Leadership Academy. “On my personal Facebook page I hosted a live stream talking about the Academy, so that’s how I got the word out,” she says. “The students are a mix of my patient community and a global online community.”

For Dr. Una, teaching goal-setting and successful habits are integral to her work in cultivating healthy kids. “The Virtual Leadership Academy idea was born out of what I do every day at work,” she says. “Say I’ve done your checkup and your body is healthy. Well, what about your mind? What about the whole child?” She continues, “I have kids who are ‘healthy,’ but struggle in school, have no idea what they want to be when they grow up, have low self-esteem. If I can assess your physical health, but I can’t help with your social-emotional health, I haven’t fully helped you.”

“Our hearts’ desire is and should be to serve our patients. But if you aren’t successful as an entrepreneur and you have to shut your clinic down, you can’t serve your patients.”Dr. Nneka Una

Non-Clinical Work: Professional Coaching

One of Dr. Una’s many extracurricular passions is professional coaching. Through public speaking events and one-on-one mentorship, she is helping physicians to build and maintain healthy independent practices, and to pursue their own personal and professional goals.

Dr. Una prioritizes work-life balance in her coaching as well. Just as she treats the whole child, she makes sure to take a whole-life approach to professional coaching, meaning the time physicians spend caring for themselves and feeding their non-medical passions. “I do some work-life balance coaching,” she says, “because physicians are some of the most depressed people out there. We’re bad at taking time off.”

Now that she’s grown her own healthy practice, Dr. Una has more time to offer her professional advice to others. “I work particularly with people who want to start their own practice, or are struggling to keep their practice open,” she says. “In the past, many physicians worked for hospital practices, so the business education we need now—it’s just not there in medical school. There are very few schools that have a Business of Medicine curriculum. I’ve met with a doctor who told me, ‘My practice is here, but I’m one bad week away from not making payroll.’” Dr. Una told that particular doctor, “We need to fix that or you need to close your practice and get a different job. That’s no way to live.”

Dr. Una’s Memoir

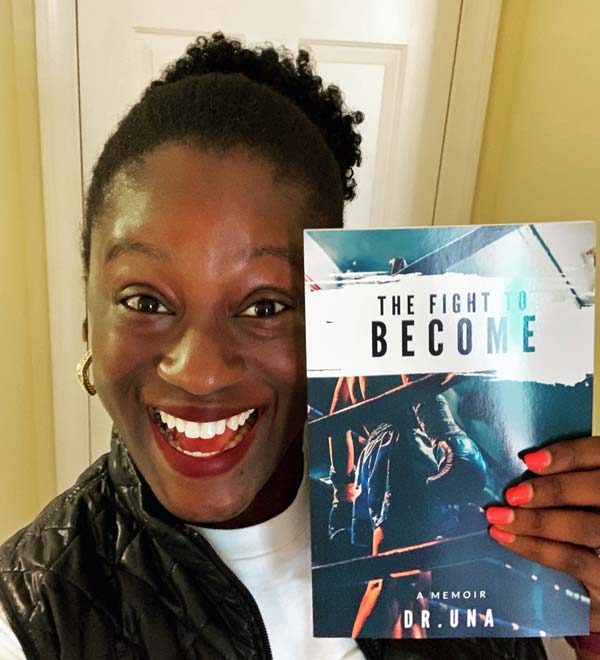

On top of her other projects, this past year Dr. Una authored and self-published her memoir, The Fight to Become. “For my birthday this year I wanted to give back, and writing this book was what I came up with. It’s easy to look at people who seem to be successful and think that they’re just lucky. They seem like a mystery. I wrote this book to demystify success.”

Dr. Una’s intended audience for the book include her patients, clients, friends, family—anyone whose fear of failure may be inhibiting them from pursuing their goals. “Everybody you see who appears successful has failed at many things,” Dr. Una says. “Maybe they’ve capitalized on opportunities differently, maybe they’ve lived out of their comfort zone longer, maybe they’ve been willing to suck, and this process has built resilience and grit. But they aren’t better than anyone else. I’m not better than anybody.” She continues, “In the book, I share the battles, disappointments, and mistakes I’ve had to face, and the lessons I learned along the way. The book is to tell my community: ‘You can do it, too.’”

Through her writing, coaching, and most of all by example, Dr. Una has helped to define resiliency and success in her community. Her practice brings families together to think about their children’s health holistically. Using this approach, Dr. Una is able to do so much more than simply practice medicine.

Emily Graf is a freelance writer, wilderness educator, and English teacher living in Colorado. She is passionate about telling stories that promote equal access to quality health care. She can be contacted at emgraf11@gmail.com for inquiries.