All students with disabilities in the United States are legally guaranteed individualized special education services, so that they have the opportunity to learn and succeed, yet many schools fail to properly help these struggling children. Dr. Adrienne Classen of North Carolina steps up to fight for these students’ rights.

Imagine a six-year-old boy heading into his pediatrician’s office for a basic well visit. The appointment will likely follow a familiar pattern: The patient is weighed and measured, his vitals are checked, vision and hearing tests are performed. Medical staff answer any questions his parents have and help them schedule the next appointment at the checkout window. Then, the doctor follows the boy’s parents down to his school, where they meet with teachers, school administrators, and civil rights lawyers to discuss the boy’s deteriorating academic performance and come up with a plan to help him access the quality education that he is legally entitled to under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

That last part might sound a little strange to most physicians, but for Dr. Adrienne Classen of Kids Count Pediatrics in North Carolina, that’s just a typical day at the office.

A Lifelong Dedication to Special Education

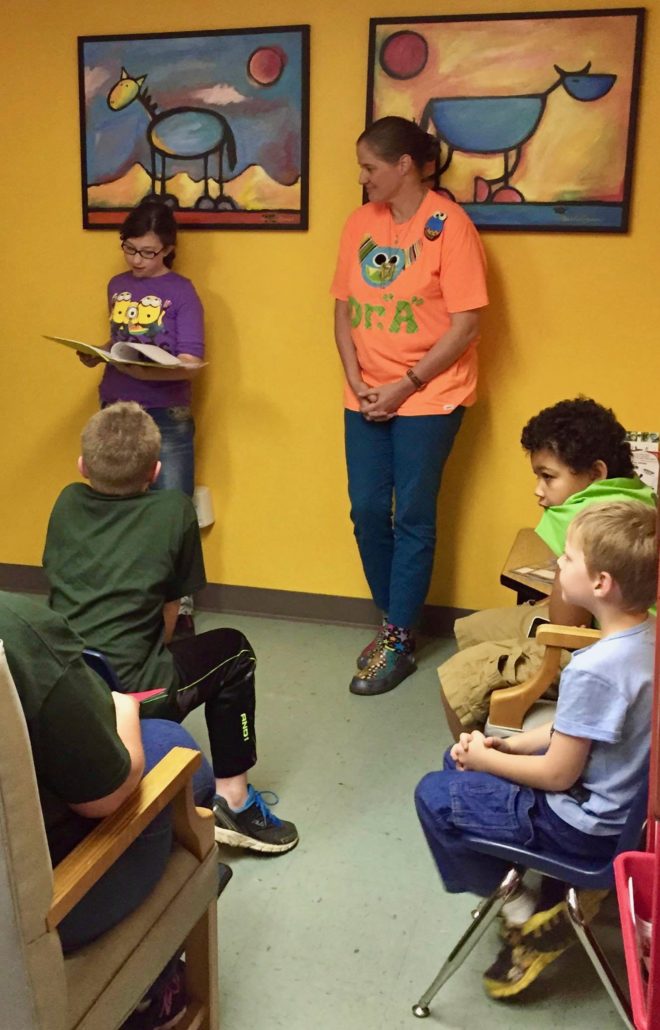

Dr. Classen, whose patients affectionately call her “Dr. A”, has spent over a decade fighting for the education rights of students with special needs in her community. Her practice, Kids Count Pediatrics, is based in Elkin, North Carolina, and serves the surrounding Surry, Wilkes, Alleghany and Yadkin counties. Nestled in the Appalachian Mountains, this rural area is home to beautiful hiking trails and picturesque vineyards, as well as crippling poverty, underfunded schools, and a vicious cycle of academic underachievement that Dr. Classen hopes to break.

Dr. Classen grew up not far from Elkin, and from an early age was exposed to the struggles of living with disabilities. Her younger sister has a severe learning disability, and didn’t learn how to read until she was in the third grade. “She was lucky because my dad was wealthy,” Dr. Classen explains. “She always got all the help she needed.” Unlike many of Dr. Classen’s patients, her parents were in a position to fight for extra services in their daughter’s school. Dr. Classen’s sister was able to receive special accommodations all the way through college, and is now a successful ecologist with over two hundred published papers. Her accomplishments stand as a testament to the power of special education services.

“I feel like every other kid should have that same opportunity,” Dr. Classen says. “If she’d been born into a poor family where she didn’t get help, she would’ve been an eighth- or ninth-grade dropout.”

At Kids Count Pediatrics, where Medicaid patients represent 87 percent of her practice, Dr. Classen encounters many children who are living that “what could have been:” struggling students whose parents don’t have the resources to fight to get them the assistance they need. The problem is compounded by underfunded and inadequately staffed local school districts. Opportunities and support for children with learning disabilities are scarce. “Kids get stuck in classes where they can’t succeed,” Dr. Classen says, “and then we wonder why they drop out. It’s hard to watch.”

The situation in North Carolina is starkly contrasted with Dr. Classen’s previous job in California’s affluent Bay Area. There, many of her patients were the children of high-powered Silicon Valley CEOs, and Dr. Classen admits she rarely diagnosed a learning disorder or felt the need to discuss academics with her patients. If a child was struggling in school, she says, “things just got taken care of.”

After several years on the West Coast, she returned to North Carolina, originally planning on scaling back her commitment to pediatrics. She hoped to focus instead on equestrianism; for a while, she’d been moonlighting as a competitive horse rider, and had moved to Elkin in order to dedicate more time to the sport. Instead, she decided to almost completely give up riding when she saw how much children in the area were struggling.

“When I saw what was happening to kids here, I was shocked,” she recalls. “I was just blown away.” Undoubtedly driven by the memory of her sister’s own experience with special education, Dr. Classen committed herself to supporting these struggling students and their families, dedicating her personal time to the fight and sacrificing the profits she could have been making continuing to practice in California. Now, over a decade later, she’s more invested than ever.

“I don’t understand why we think that it’s a good idea to take cute little five-, six-, seven-year-olds, give them failing grades and terrible test scores and tell them they’re not good enough – and then give them no help!” Dr. Classen’s voice radiates with emotion. “It’s not fair. I know life isn’t fair, but I hate it when it’s not fair. It really pisses me off.”

The Twisted Maze of Special Education Law

“I’ve learned a lot about school law after twelve years,” Dr. Classen says, with only a hint of pride in her tone. She’s certainly earned the right to boast after becoming an expert in the complex field of special education law. The legislation is built around indefinite definitions, and involves so many acronyms that reports read like alphabet soup. Each state and sometimes even each school district has its own specific regulations, and because each student needs a personalized plan, every case is unique and unprecedented. It’s enough to give any overtired parent or underpaid pediatrician a headache.

However, at the core of all the convoluted legislation is a simple mission, which pediatricians will find familiar: caring for our nation’s children and giving them aid when they are in need.

Any child in the United States who has a disability that hinders their academic performance is legally entitled to special education services. These benefits are conferred under one of two federal laws: either the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990, that ensures all students, regardless of disability, have access to an equal education; or the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in any institution which receives federal funding. Students whose special education is regulated under IDEA have an individualized education program (IEP), a legally binding document which describes the services the child will receive and other information pertinent to their education. A 504 plan is a similar legal document that is used for students protected under the Rehabilitation Act. 504 plans include generally the same information as IEPs, and are named for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which specifically prohibits discrimination in schools.

The assistance these plans provide can range from a little extra time on a test to a dedicated one-on-one aide for the student, and the services they ensure can often mean the difference between success and failure. Approximately 13 percent of all students in the United States have an IEP1 , and an additional 1.5 percent are served by a 504 plan2. In 2015, 80% of students relying on special education services graduated high school with a diploma or an alternative completion certificate3.

For a student to qualify for an IEP, they must have a hearing, speech, visual, or orthopedic impairment, a serious emotional disturbance, a traumatic brain injury, a specific learning disability, deaf-blindness, or an “other health impairment,” and this disability must have a direct adverse effect on their education4. After an official request by the child’s parent, the school will formally evaluate the child. When it is determined that they meet IEP requirements, an IEP team consisting of educators, school administrators, parents, and sometimes the child’s physician, meets to craft an education plan that fulfills the student’s unique needs.

The definition of a disability under Section 504 is much broader than the more restrictive terminology in IDEA, so 504 plans are a great alternative for children who don’t qualify for an IEP, or who previously had an IEP but progressed out of it. A student can be a candidate for a 504 plan if they have a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity”5. This wording gives advocates like Dr. Classen ample leeway to argue that a student needs to be on a 504 plan, but because it includes such a wide swathe of students, 504 plans are typically less elaborate than IEPs. Dr. Classen stresses that 504 plans can still be beneficial for the right students. Children with attention issues such as ADD or ADHD are prime candidates to benefit from a 504 plan in the likely case that their situation doesn’t merit an IEP.

“I’m pretty sure it’s every child guaranteed an equal education, not children in California guaranteed a better education than the children in North Carolina.”Dr. Adrienne Classen

The Patient Population Factor

IDEA and Section 504 are federal laws that ensure special education services for all children in the United States who need them. Despite some regional specifications, this legislation theoretically applies equally to every school district, in every classroom, and at every desk. In Dr. Classen’s experience, this isn’t the case.

Once, she recalls, she was talking with a lawyer from the Office of Civil Rights, a legal aid agency within the U.S. Department of Education to which she often refers families. The lawyer told her that she’d been sending them a lot of cases since she’d started practicing in North Carolina, and that they often see this kind of activity when a physician moves from a hub like New York or California to a more rural area. “We start getting all these cases from them,” Dr. Classen paraphrases the lawyer, “but you can’t expect kids to get the same kind of school there that they would in California.” She remembers responding, somewhat sarcastically: “I’m pretty sure it’s every child guaranteed an equal education, not children in California guaranteed a better education than the children in North Carolina.”

So, why do these two communities handle special education so differently? Dr. Classen doesn’t need much prompting to come to an answer. “They don’t take care of poor children in the United States.”

It is no secret that public education is underfunded across the United States, and in impoverished communities, like those Dr. Classen serves, the lack of resources is even more severe. A very small portion of an already small budget is allocated to special education services. In order to meet these stringent financial requirements, school administrations overlook students’ needs for special accommodations, and sometimes actively deter parents from requesting IEP evaluations for their children.

Dr. Classen stresses that it isn’t the children’s teachers who try to withhold special education from children who need it. More than once she’s had a teacher come up to her after an IEP meeting to thank her for advocating for a child. “They say to me, ‘I just want to let you know, I agree with everything you said, I just can’t say it.’ Their hands are tied.”

A key facet of the IDEA legislation is the Child Find mandate, which dictates that states and school districts must locate, identify and evaluate all children with disabilities who require educational assistance. In theory, the school would look for students showing signs of a disability, watching for indicators like low End-of-Grade (EOG) test scores, and take the initiative to enroll these students in special education. In reality, Dr. Classen recalls seeing patients who were nearly failing out of their classes and receiving no special assistance at all. She wonders: “What is the point of doing the testing?!”

If the schools overlook these warning signs, a child’s parents are left on their own to seek out special education services. In rural North Carolina, Dr. Classen observes that many of her parents, who may be undereducated themselves, don’t know what red flags to look for. At appointments, she makes it a point to bring up the children’s academic performance and ask specific questions about their grades and EOG scores. If she finds a cause for concern, she encourages the parents to file a formal request with school administration for a disability evaluation.

Dr. Classen believes that the schools she works with will sometimes try to deter the parents from pursuing these requests. They use tactics which prey on the parents’ natural fears about their child and their own ability as a caretaker, or exploit the parent’s lack of education and financial resources. Dr. Classen finds that parents in low-income communities are especially susceptible to these tactics, and are less likely to advocate for themselves and their child in the face of pressure from a strong institution like a school administration. “They get kicked around everywhere,” she says, and they lose the motivation to fight back. Dr. Classen doesn’t let them stay down for long. She works hard to encourage their efforts and give them the confidence to stand up to school administrators. She says: “I think of what I do as being a cheerleader.”

“What we say as doctors to parents has a lot of power,” she notes. “It can be so significant to just tell them: You are right, and you are being a great advocate for your kid, and don’t you dare let them make you feel like you’re a bad parent! I think a lot of times just telling people that they’re doing a good job and supporting them is so important.”

In communities like Dr. Classen’s, where these parents so rarely hear positive feedback, her encouragement makes a huge difference. Parents praise her personal touch in online reviews. “Thank you for always treating us like we were people,” one parent writes, “and not just another case.”

Supporting Students and Promoting Education

Students with disabilities and their families face many challenges, and Dr. Classen is committed to helping them in any way she can. She emphasizes that the most important thing she does to help her patients and their families is offer support and encouragement. It’s the most direct way she assists them, and she suggests that it’s the first thing to do for any pediatrician who wants to get involved in this cause. It’s an easy, but meaningful, way to help.

Dr. Classen also will send letters to school administrators on parents’ behalf. “I make sure I send it certified mail,” she says, “so the school can’t say they never got it.” Certified mail also marks the date when the letter was sent and received, which is important because IEP evaluations legally have to be done within a certain time frame after the request is made.

She often joins parents at IEP meetings, lending her voice and presence to the student’s cause. As a medical professional, she has valuable insight, and can steer the team toward a comprehensive and truly beneficial IEP. As an advocate for her patients, she can help prevent the administrators from bullying parents into accepting an inadequate special education plan.

Dr. Classen also recognizes that, sometimes, the special education assistance a school can or will provide just isn’t going to be enough. She’s involved with several national organizations that aim to help children learn to read, and she has a mini-library in her waiting room where parents can leave old books and take new ones. She’s helped establish scholarships for online therapy programs designed to help with learning disabilities like dyslexia, and gotten computers donated to low-income homes so that they can access these resources.

Dr. Classen works with Reach Out and Read, a national nonprofit that encourages literacy and provides books for children and parents to read together. She is also involved with the organization First Book, which specifically targets low-income families and provides them with affordable books and other educational supplies. Through these programs, Dr. Classen is able to get high quality books at reduced prices and hand them out to her patients when they come to her office. At Kids Count Pediatrics, she says, they make it a mission to give a book to every child at every visit, regardless of age or disability.

“Just getting books into their hands can make a big difference,” Dr. Classen says. She sees these programs benefiting not only the children, but also their parents, as she encourages her patients to read together as a family. This is especially important, Dr. Classen stresses, because many of her patients’ parents struggle with reading themselves, and likely wouldn’t take the initiative to read at home without these programs. In a community where many of the parents are high school dropouts, this can be a significant step towards breaking a cycle of undereducation and academic apathy.

Why It’s All Worth It

Every small step counts when tackling an issue as complex as special education in America, and Dr. Classen is certainly taking giant leaps. But she doesn’t deny that there is still so much work to be done.

“We need more really good pediatricians out in areas like this,” she says, and encourages all pediatricians to be more involved in the academic sphere of their patients’ lives. It isn’t easy or financially practical (just like most of pediatrics), but Dr. Classen can personally attest to how rewarding it can be. The benefits she’s observed in her patients, their families, and her entire community are significant.

“It’s a mess,” she admits, “but at least the kids are cute.”

To help students in your own community, check out these online resources

- Parent advocacy groups in each state: copaa.org and ndrn.org

- Online communities where parents can find support and more information: parentcenterhub.org and p2pusa.org

- More information for health-care providers about learning disabilities, created by the National Center for Learning Disabilities: ldnavigator.ncld.org

- Make a complaint to the Office of Civil Rights: www2.ed.gov and ocrcas.ed.gov

- Get in touch with Disability Rights Advocates, a nonprofit legal center that provides free representation to people with disabilities whose civil rights have been violated: dralegal.org

- More information about special education law: wrightslaw.com

- A sample letter for parents or physicians to send to schools, provided by CHADD

[1] “The Condition of Education – Participation in Education – Elementary/Secondary – Children and Youth With Disabilities – Indicator April (2018),” National Center for Education Statistics, last modified April 2018. nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp ↑

[2] “Analysis of Students with Disabilities Served under Section 504,” The Advocacy Institute, last modified August 2015. www.advocacyinstitute.org/resources/504analysisCRDC2012.shtml. ↑

[3] “39th Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2017,” United States Department of Education, January 2018, 63–65, www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2017/parts-b-c/39th-arc-for-idea.pdf. ↑

[4] Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 20 U.S.C. § 1401 (2004). sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-I/1401/3/A ↑

[5] “Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Handicap in Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance.” 34 C.F.R. 104 (2000). www2.ed.gov/policy/rights/reg/ocr/edlite-34cfr104.html ↑

Sami Kassel is a resident of Boston, Massachusetts. She recently graduated with a B.A. in cultural anthropology from Boston University, and plans to continue her education in a graduate program. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, reading, cooking, and indulging her love for craft beer.